Mar 30, 2015 - 12:00 pm

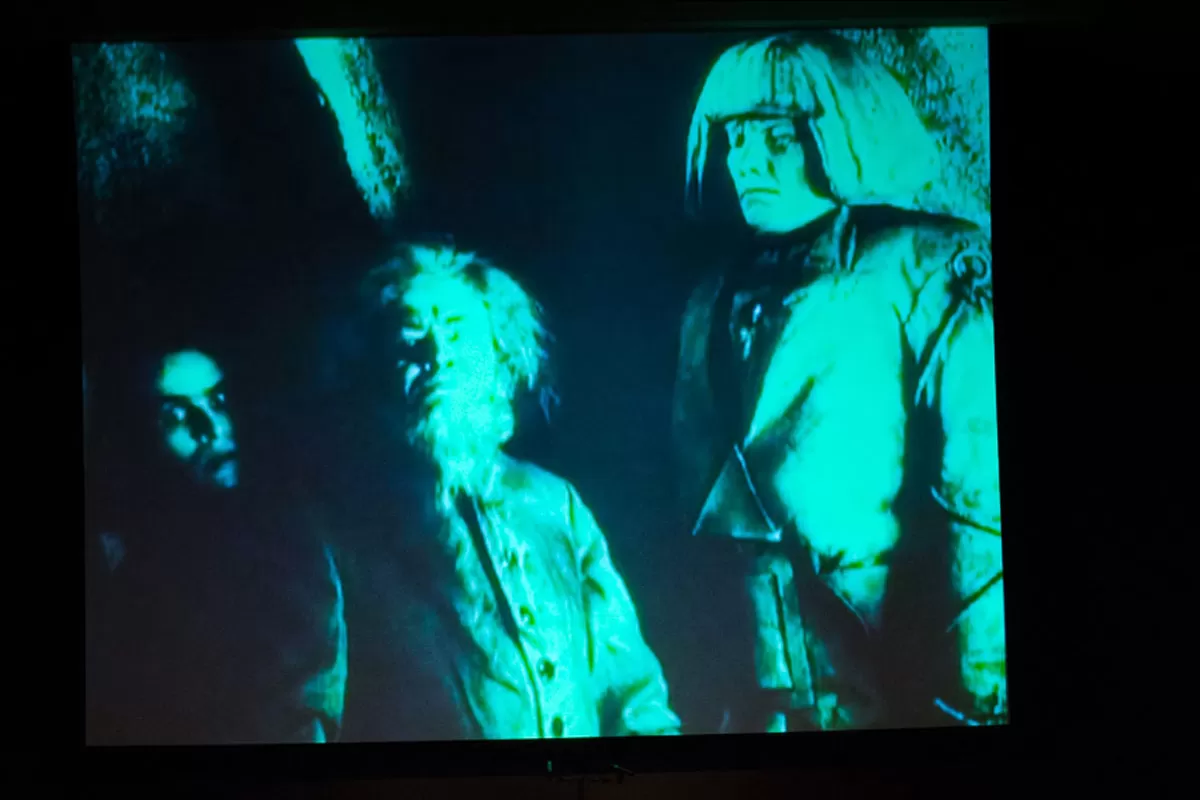

This spring MOR explored Jewish legends, featuring music to The Dybbuk and a complete screening of the classic 1920 silent film The Golem, accompanied by a live performance of Israeli composer Betty Olivero's exhilarating klezmer-infused score. This iconic film mirrors complex perceptions of Jews and Jewish identify at a pivotal time in early 20th century Germany. Guest conductor Guenter Buchwald joined us from Freiburg, Germany to bring his rare mastery of the silent film repertoire to Seattle audiences. Those who attended our screening of The Golem in 2008 will remember Laura DeLuca's dazzling clarinet solos. On this special evening, we also welcomed the return of the talented 13-year-old violinist Takumi Taguchi in a soulful melody by Joseph Achron.

"Olivero's music...generated striking moments - a haunting solo clarinet wailing during a synagogue as the city burned." - Mark Swed, Los Angeles Times

"Betty Olivero: One of the most admired composers in Israel in the early twenty-first century..." - Jewish Women's Encyclopedia

"Everything performed by MOR needs to be heard again." - The Seattle Times

Joseph Achron

Hebrew Melody (1911)

Violin: Takumi Taguchi, age 13

Piano: Mina Miller

Music of Remembrance concert, March 30, 2015

Illsley Ball Nordstrom Recital Hall - Benaroya Hall, Seattle

Mina Miller, Artistic Director

Click here to view The Golem in our 17th season brochure!

March Concert Program:

Hebrew Melody (1943)

Joseph Achron

Takumi Taguchi, violin; Mina Miller, piano

Dybbuk Dances (1941)

David Beigelman

Mikhail Shmidt, violin; Laura DeLuca, clarinet

The Dybbuk Suite (1922)

Joel Engel

Laura DeLuca, clarinet; Mikhail Shmidt, violin; Leonid Keylin, violin; Susan Gulkis Assadi, viola; Mara Finkelstein, cello; Jordan Anderson, double bass; Matthew Kocmieroski, percussion

The Golem (1997)

Betty Olivero

Complete score to accompany the 1920 silent film screening

Guenter Buchwald, Guest Conductor

Laura DeLuca, clarinet; Mikhail Shmidt, violin; Leonid Keylin, violin; Susan Gulkis Assadi, viola; Mara Finkelstein, cello

Original film "Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam" (1920) directed by Carl Boese and Paul Wegener; written by Henrik Galeen and Paul Wegener

About the Music

Hebrew Melody (1911)

Joseph Achron (b. Lodzdzieje, Lithuania, 1886 – d. Los Angeles, 1943)

The Dybbuk Suite, Op. 35 (1922)

Joel Engel (b. Berdyansk, Crimea, 1868 – d. Tel Aviv, 1927)

Dybbuk Dances (Lodz Ghetto, 1941)

David Beigelman ((b. Ostrovtse, Poland, 1887 - d. Auschwitz, 1945)

For a brief period at the start of the 20th Century, Czarist Russia was the center for Jewish art music composed in a style that became known as the St. Petersburg School, a movement that applied techniques of Western classical music to klezmer and cantorial traditions, seeking source material in the secular tunes and religious melodies of the Pale of Settlement. The movement was institutionalized in 1908 with the founding of the Society for Jewish Folk Music in St. Petersburg. In 1912, branches of the Society opened in Moscow and Kharkov. The Society organized concerts of Jewish music in numerous towns, and by 1913 had over 1,000 members and branches in seven cities, providing intellectual, artistic and practical support for Russian Jewish music. After the Russian Revolution, the Society was confronted by Soviet anti-religious ideology. Following several attempts to refashion itself, the Society was disbanded in the mid-1920s.

Both Joseph Achron and Joel Engel played important roles in the Society. Although Achron was a relative latecomer to the Society, his experience in it was a strongly formative one that set a path for much of his future career. With the Society in decline, Achron moved in 1922 to Berlin , where he and fellow composer and Society member Mikhail Gnessin briefly managed the Jewish music publishing company Jibneh. After a brief stay in Palestine, Achron immigrated to America in 1925, first settling in New York. In 1934 he relocated to Hollywood, where he composed for films and continued to tour as a concert violinist. His third violin concerto was commissioned by Jascha Heifetz, a fellow émigré in the film capital. His friend Arnold Schoenberg eulogized Achron as “one of the most underrated modern composers.”

The 1911 Hebrew Melody was one of Achron’s first compositions after he joined the Society. It is based on a theme he remembered hearing in a Warsaw synagogue in his youth. The piece was first performed in St. Petersburg in 1912 at a ball-concert given by an adjutant to the czar, where Achron played it as an encore. It remains his best-known work, and has been played and recorded by a list of violinists that includes Jascha Heifetz, Nathan Milstein, Mischa Elman, Henryk Szeryng, and Itzhak Perlman.

Joel Engel was a founding member of the Society and he had a key role in organizing its first concert in 1908. In 1912 he joined the Jewish writer and ethnographer S. Ansky in an expedition searching the Pale of Settlement for the folk songs of Jewish communities. It was in the shtetls that Ansky discovered and grew fascinated by the legend of the dybbuk – an often-malign spirit of a deceased person that inhabits and takes control of somebody still living. Ansky was inspired to write the play “The Dybbuk, or Between Two Worlds,” in which a young woman is possessed on the day of her wedding by the soul of a brilliant Talmudic scholar who died of unrequited love for her. Engel composed his Dybbuk Suite in 1922 as incidental music for the play, which went on to become a cornerstone of Yiddish theater in Europe and America.

Two decades after the play’s premiere, the violinist, conductor and composer David Beigelman was one of the many thousands imprisoned in the Lodz Ghetto. Before the war, Lodz, in central Poland, had Europe’s second largest Jewish community, smaller only than Warsaw’s. Its vibrant Yiddish theater life included frequent shows by leading companies, and The Dybbuk was familiar to audiences from performances by the Vilna troupe (which premiered The Dybbuk in 1920), and Habima, the Hebrew theater group which started in the Soviet Union and made the play its signature piece. Under the ghetto’s conditions of unimaginable oppression and suffering, this work of theater represented a reminder of what had once been normality, and of the continuity of Yiddish tradition. In the Lodz Ghetto, this work was performed by a solo violin as incidental music to the play. We have taken the liberty of including a solo clarinet, and the two instruments share these moving and evocative melodies.

The Golem (1997)

Betty Olivero

(b. Tel Aviv, Israel 1954)

Paul Wegener created his silent film The Golem: How He Came Into The World at time of tumultuous change in the landscape of European Jewish life. By 1920—the year the German Workers Party changed its name to the National Socialist German Workers Party—the conflicting currents of Jewish assimilation and separation were converging with an increasingly virulent anti-Semitism. The director’s own biography illustrates that tension: Wegener, once a pacifist, was later honored by Josef Goebbels for his production of Nazi propaganda films. Wegener co-wrote and co-directed The Golem, and also portrayed the Golem character. The film was shot by Karl Freund, the lighting legend behind Metropolis and Dracula. (After emigrating to the U.S., Freund became head cameraman for I Love Lucy.)

Wegener produced three Golem films, but only the third – The Golem: How He Came Into The World – has been preserved. Rabbi Loew, responding to the Emperor’s decree expelling the Jews from 16th-century Prague, creates the Golem and brings him to life. The Golem saves the ghetto, but he soon slips from the rabbi’s control. The story is rich in symbolism and allegory. Some Jewish thinkers have seen the legend as a depiction of difficult moral choices faced by those confronting the threat of destruction, and a complex allegory of the dangers courted when invoking divine intervention for earthly ends. For German film audiences, The Golem contained provocative imagery of Jews and Jewishness, and the film’s impact was social as well as artistic. Olivero’s score brilliantly reinforces the cinematic effects of this classic German expressionist film, combining folk styles and contemporary techniques. Some of the music has its genesis in klezmer tunes, and another melody quotes from “Place Me Under Thy Wing.” The music, seamlessly integrated with the film, blurs the lines of memory and fantasy, history and myth.

About Music notes by Mina Miller. Copyright 2015 Music of Remembrance.